For my first twenty-six years I mumbled and stumbled along, subjected to lots of ups and downs prior to my arrival, a young man with a northern accent, at Corsham Station in June 1962. I had travelled by train from Paddington, for an interview with Clifford Ellis, Principal and Founder of Bath Academy of Art.

Returning from Italy in that year I had been offered several jobs at Art Schools that were about to embark on new courses, in order to achieve Dip AD status. They were intent on boosting their lecturing staff, so I was looking for a job at the right time. A Royal College graduate and Rome Scholar would be good on any staff list. Leeds, Wolverhampton and Wimbledon all made offers of full time or part time posts, but Corsham was my choice. I had been primed for the Academy while I was in Italy, by Irena Hale-White, a former Corsham student (pupil of ‘Kenny’ Armitage) who lived in Anticoli while I was there.

I had had an interview at Liverpool College of Art, where I was told that drawing and modelling from life were to be removed from the syllabus – that figurative sculpture was out and abstraction in. This of course did not suit me then, having spent more than half of the last six years working from the model. I didn’t take the job, it was offered to me by Principal Norman, formerly of Sunderland Art College, (after four years study at Sunderland I had failed to gain a National Diploma). Anyway the job at Liverpool was full-time and I didn’t want that, I was a sculptor not a teacher and would take on only enough teaching that would support my family and my work.

I discovered on my journey to Charlotte Street that I had short arms. I was wearing my wedding suit, charcoal grey, bought from The Scotch House in Knightsbridge and pointy black Italian shoes, a narrow tie with horizontal stripes, which I still have and wish to wear again if a tie-wearing occasion ever arises. I was carrying a heavy portfolio, packed full of life drawings and photographs of sculpture, window-mounted on thick card. It was very heavy and extremely cumbersome; just too wide to fit under my arm, the arm was stretched and my fingers were numb. I walked along Charlotte Street to Adrian Heath’s residence exceedingly lopsided.

Adrian had asked two other RCA graduates – Clinch and Arnatt – if they were interested in teaching at Bath Academy of Art, but John Clinch and Ray Arnatt already had good jobs at Nottingham and Chelsea respectively. They had advised Adrian, “Ask Pennie, he’s coming back from Rome soon.”

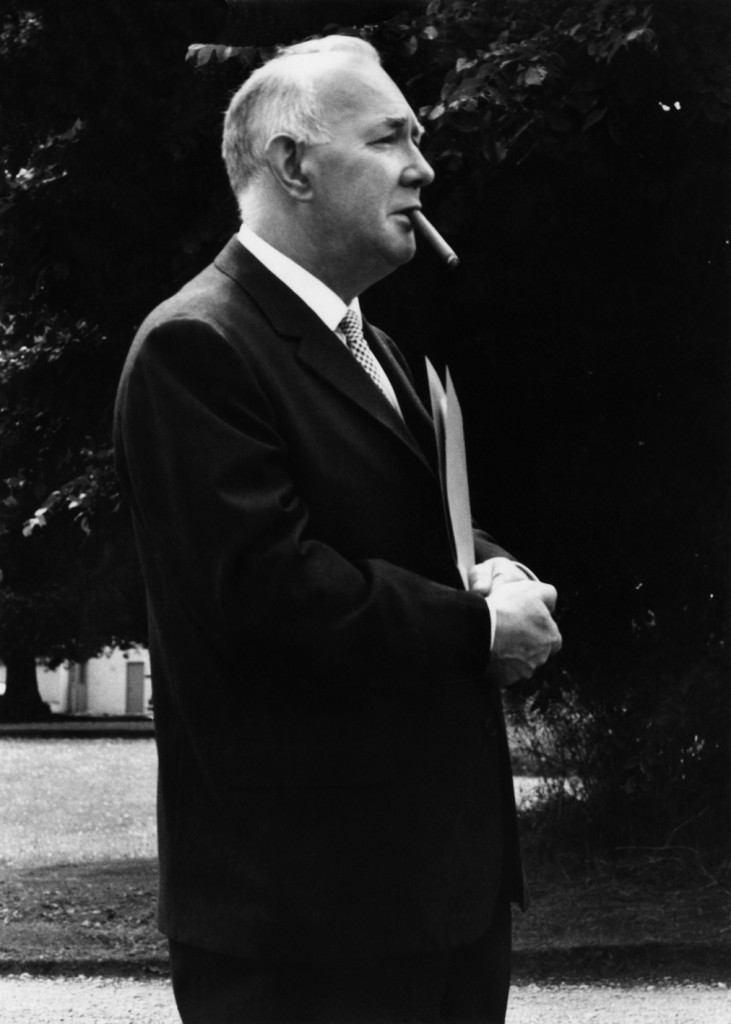

As far as I remember, the interview with Adrian did not last long. He had been asked by Clifford Ellis to find an artist who was also technically adept! Someone who had experience with the traditional processes, casting from clay to plaster for example, making armatures and carving. The interview itself was memorable because it took place upstairs in a comfortable room over-looking Charlotte Street. I was invited to sit in an Eames chair and Adrian made me possibly the worst cup of tea I have ever tasted. Perhaps it was a very special blend, but so unlike anything I’d ever had before, I found it undrinkable. Adrian sent me to Corsham to meet Clifford Ellis in person.

Alighting at Corsham’s very pretty station I was met by Mr Buckle in chauffeur’s uniform. He relieved me of my portfolio and put it in the boot of his black Austin, I sat on the leather back seat and was driven up Station Road along the High Street into Church Square. We went through the open gates of Corsham Court, up the drive and left, to the Blue Door. It was a journey of perhaps four minutes.

I was amazed to come upon such a beautiful Country House sitting behind the High Street and the Flemish Weavers’ cottages, and close by the church.

Evelyn, the Principal’s secretary, was waiting at the Blue Door to welcome me and escort me from the ground floor to the first, to meet Clifford. We stood together outside his office, overlooking the staircase and hall and the largest oil paintings I had ever seen. I was still clutching my portfolio and consequently leaning over a bit. He handed me a small roll of paper about the size of a cigarette, in fact for one moment I thought it was a roll-up. Clifford directed me back down the staircase and down the drive to the building on the right of the gate called the Riding School, the studios where Sculpture was taught. I was to give the note, for that’s what it was, to John Hoskin. It was a beautiful June day and hot, I was beginning to be very sweaty as I carried my portfolio between immaculate lawns towards the two Sculpture buildings. John was there, in friendly form, he unrolled the thin strip of paper and showed me the neat-pencilled instruction, “If he’s any good keep him on.” It seems to me that I have been in Corsham ever since!

To begin with, my teaching timetable was sculpture on Fridays and Life Drawing on Saturday mornings. This latter took place in the Barn. It had started some time before as a voluntary event open to all, but when I arrived at Corsham this class (of beautiful young women and very few young men) was on the timetable.

My students were for the most part taking the Institute of Education Course – training to be Art teachers. There was also a smattering of NDD students, plus Tim Threlfall, an independent student working in Sculpture full-time. The Sculpture course was part of a wide-ranging syllabus. My first group consisted of one male and nine females: I remember them well.

At the end of term assessment meetings in the Board Room, to the surprise and consternation of the assembled teaching staff around the long walnut table, Clifford revealed he knew more than most of us about our student’s progress and the sculptures or paintings they had been working on. It was known that in the evenings he made a regular tour of inspection of all the studios.

Meanwhile my adventures with Adrian continued. He sold me my first car, a Ford Prefect, for £40, (paid in monthly instalments). It was a car that was very reluctant to start on damp mornings. I kept my drawing board under the bonnet overnight, to absorb any condensation. I had my money’s worth out of the Prefect before the engine died, just outside Chippenham. A reconditioned engine would have cost me £70, which I did not have and could not borrow, so the little car was abandoned.

Bob Davis, Marlene’s father, was a long-time friend of Adrian’s, they were good companions. Bob the builder undertook various jobs around the Heath estate, maintaining his little house in Pickwick, his larger cottage at Freshford and the family home in Monkton (where Adrian’s mother lived).

Bob was a man without transport, telephone or bank account. There were times when he needed a lift to his place of work; if all else failed he would ask me. So it was that I spent the day scraping wallpaper off the walls inside the Freshford house, and another time chopping down nettles, and then clearing the drive to his mother’s mansion. This was when I wasn’t teaching and on a day when I was short of money, which was every day in the 1970s.

However there was an occasion when I changed my overalls for smart casual to have dinner at Freshford: Marlene and me and Adrian and Julia, the most charming of his several tender friends.

Adrian was kind to Marlene. One birthday he gave her a lithograph (Untitled Artists Proof 1972) that is presently on loan to the exhibition Corsham Painters and Sculptors – Revisited at Corsham Court. Another gift was Towards Sculpture, Strachan’s book of sculptor’s drawings.

It is of some interest that early Heath abstractions would have qualified him for membership of the Systems group, led at Corsham by Malcolm Hughes and Michael Kidner. However in the late sixties there was a social and political divide between the intelligent and the intellectuals and both factions were on opposite sides; the RAF ratings and the officer class, Socialist and Tory.

Why were these two conflicting strands parts of the same Painting Course? Two disparate dogmas were in operation: figurative, landscape with strong subject matter on the one hand, and the simplicity of trying to establish order out of the recent chaos on the other; the half a century of conflict, that had seared the lives of Adrian and Malcolm as well as several others at the Academy.

Although there was no animosity between the two groups, a certain coolness was evident. Hughes was the most dismissive, impatient that Heath, one of the ‘best artists in England’, should, as a mature painter, move from the brilliant abstractions of the fifties and early sixties to figurative work and often from a model.

The question remains: how and why were these two strands held together as two wings of the same course? Was it that Clifford, with his appreciation of the Bauhaus values, thought a Schematic pathway through art education rather than a smooth Fine Art route, was more beneficial to aspiring teachers?

Shortly after I began teaching at BAA, I was asked to draw up plans for an office. Clifford Ellis and I stood looking at the space – the wall between the sculpture workshops, from the casting studio to the large general studio. He said, “Draw me a plan and an elevation.” During the holidays I made a very basic drawing of a lean to, a wooden wall with a door in it and a corrugated roof, half of which was Perspex. When Clifford saw my simple plan he kindly made no comment, except that “We’d better have a window in the door.” He said something about being able to see what was going on inside!

The office, a ‘private’ place where tutorials could be held, away from noise of the workshops, was quickly constructed. Furnished with an old filing cabinet, two chairs and a table, a telephone was installed. I used it as my administrative centre on Monday and Tuesday but what John Hoskin did in it on Thursday and Friday I can only surmise. From the little he told me the time he spent in there was more exciting than mine.

Surprisingly this little building has survived fifty years. It is still standing, although it was scheduled to be demolished, as the University renovates the buildings and facilities at Corsham Court Campus. But there was a stumbling block. The local Planning Office put out a restraining order and has insisted that my little edifice, because it is within the curtilage of Grade 2 listed buildings, was completely restored!

Sculpture at Corsham took place in premises that were too small and too close to the Church and the Church Square, never a good location to have workshop activities.

The need to adapt to the demands of the new Dip AD course and the consequent increase in student numbers meant a move of Sculpture from Corsham Court to the Beechfield Campus, to occupy a place alongside Painting, Ceramics and Graphics studios. The new Sculpture building was originally designed as a structure to cover Primary School playgrounds, creating a large dry area. It was primarily a roof with a large span, borne by the walls only, leaving the interior space uninterrupted except for a few supporting columns. The Wood and Metal workshops were housed in extensions along one side of this main building. Manned by the newly appointed technicians, Bill for metalwork (for a short time and then taken over by the inestimable John Repper), Geoff Hawkins in woodwork, James Castle in the casting shop. There was no Foundry to begin with, however, Bernard Meadows had cautioned us, during a Validation visit, that no Sculpture School worthy of the name was without a working foundry. So bronze casting had been planned for and finally installed at Beechfield, operated initially by the priceless John Webb.

At that time I was teaching two days a week for thirty-six weeks a year and by choice, it has to be said. It was the full-time staff that took all the planning decisions. I was peripatetic going to other schools around the country, earning extra cash and learning how other Fine Art courses operated. For more than twenty years I was almost unique in that respect, more knowing than other member of staff at Corsham, about the Fine Art courses in the schools that we had to compete with for student applications. In other words keeping an eye on the competition. Anyway, apart from teaching to earn money, I was pre-occupied with my own work. After John Hoskin had left Corsham to go to Lancaster, I felt deserted and unsettled. The idea of moving to another college appealed to me, Brighton Polytechnic was top of my list (James Tower was then Principal Lecturer there). Then my need for a change was, to some extent mollified, at least deferred, by my Fellowship at Gregynog Hall.

After winning that prize and relishing my Reader status at the University of Wales, and having had six solo exhibitions of sculpture, drawings and prints in a year, I considered that I was under-valued at Bath Academy. I hovered somewhere between the permanent staff and the star visitors, my long service notwithstanding. Kenneth Hughes was Principal Lecturer, Peter Green had been appointed fulltime, Laurie Whitfield was a regular part time teacher, adding up to three men from Manchester.

But change happens, as it did at Corsham when Colin Painter became Head of School. I sensed that I was more valued as an artist and teacher by his new regime. After all, I had won the hand of Marlene, the Fine Art Secretary, the fairest of them all at BAA. Not long afterwards, I was offered an Associate Lectureship. In 1986 the Art School left the Elysian Fields of Corsham and moved to Bath, to the College of Higher Education at Sion Hill, where I was in charge of Sculpture.