It was my brother’s friend Norman Jackson who introduced me to conjuring. I was twelve and living in Station Road, Wallsend at the time. He also introduced me to Doreen, she lived next door to Norman and was a year or two older than me, I was besotted.

I bought the little books The Young Conjurer, parts one and two, (I still have these) and began to practice magic seriously when the family moved to Saltburn Road in Sunderland. From the local library I borrowed and read avidly about the magic of Maskelyne and Devant and the adventures of Harry Houdini, in the hope of acquiring a little of their magical prowess.

Mostly my tricks were adaptations. Before TV there were Music Halls or Variety Theatres in every city; dancers, jugglers, comedians, ventriloquists, acrobats and conjurers performed twice nightly with a star act topping the bill. I would be there, in the Upper Circle, whenever a magic act was playing; at the Empire Theatre in Sunderland or the Theatre Royal in Newcastle. For star performers, (the great illusionists who would entertain for the whole evening rather than a ten minute slot), I would travel further afield.

On two occasions in the early 50s I saw Europe’s master magician Kalanag, assisted by the beautiful Gloria. At the wave of his magic wand and the recitation of Sim-Sala-Bim, he could make a limousine disappear. It has been said of Helmut Schreiber, Kalanag’s everyday name, that he was also involved in the disappearance of the Reichsbank Millions towards the end of the World War 2.

Between the first and second house, I’d go around to the stage-door to ask for autographs and to talk ‘magic’ with the artistes. At the Empire I was known well enough to get access backstage. This was a different world where that which was glittery and amazing from the stalls was suddenly garish, even grotesque, when observed close to.

One night in 1954 I stood in the wings, while Issy Bonn sang Oh Mein Papa to Eddie Calvert’s Golden Trumpet and watched the spittle dripping on to the stage from the bell of his instrument. During one interval I met Ali Bey, the Great Arabian Wizard, he was not an Arab although he dressed like one on stage, he was in fact David Lemmy and a very skilful exponent of sleight of hand. I was shown into his dressing room where he lay on the floor, resting his back. He had had an accident when a Safety Curtain was lowered on to him as he took his bow. As we talked he remained on his mat eating a custard tart. A image that caused me revise my notions of show business.

Tommy Cooper was just as funny setting up his props between acts, as he was when performing. He showed me a new trick – a pocket illusion – a sixpence passing through two matchsticks. A kind man to give me his time and encouragement.

One summer in Sunderland, a huge motorised trailer, Hollywood style, parked in the alley next to the Empire. It was the mobile home of American movie star, John Calvert (and his wife and stage assistant Tammy). He was there to perform for a season in Sunderland as a grand illusionist, although he was better known as the debonair detective Michael Lanyard, aka The Falcon in films such as Appointment with Murder. I was quick to ask for signed photographs, I remember his accommodation better than his stage-act, however he is still making magic at 101!

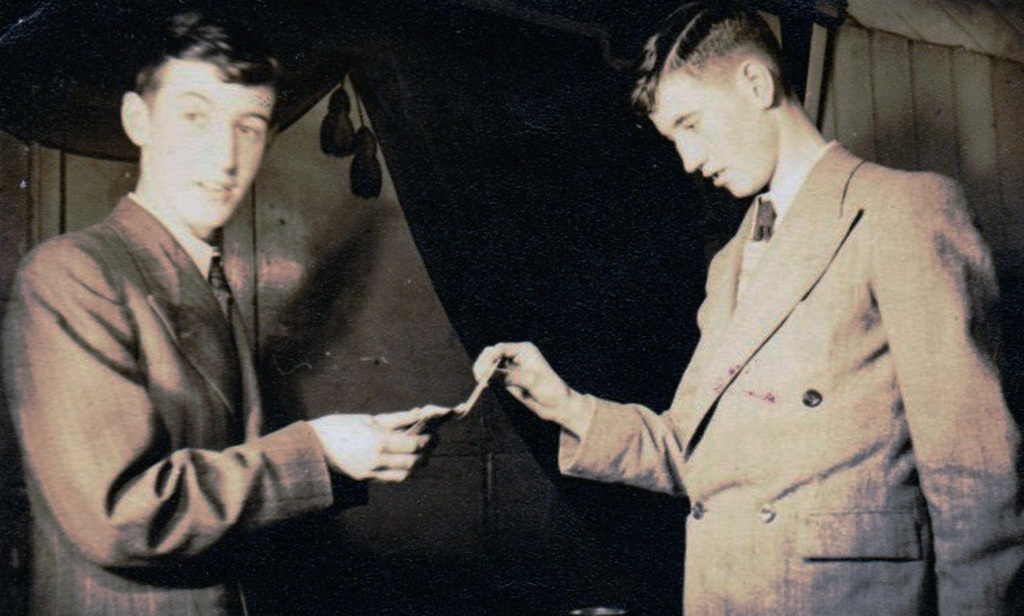

I performed at children’s parties and for senior citizens. I was a regular at the Church of Latter Day Saints. My fee was 10 shillings for a half hour act. Usually I constructed, painted and decorated my own ‘apparatus’, as we in the business called our bits and pieces. I carried costume and tricks in a small black suitcase with a white rabbit logo on the lid, relying on my host to provide a small table. I wore my ubiquitous grey double-breasted suit. Each illusion was accompanied by a fanciful story narrated in the style of the Mysterious Orient. Presenting the Rope in the Bottle trick, I declared, “Whosoever can make this rope remain fast in this bottle, shall marry my daughter, the Princess.” The trick concluded with the large bottle hanging from a silken cord, and my patter ended when I told the ‘spellbound’ audience that it was a goat-herd, a boy from a humble background, who had solved the puzzle and got the girl!

The most demanding of my deceptions was with look-a-like billiard balls, a sleight of hand trick that depended for success on a high degree of manipulation and a lot of practice. Although Pennies from Heaven was my most skilful illusion; catching coins in the air, dropping them with a clang into a decorated tin. I closed my performance with the Rabbit from a Hat, in reality a pierced card cylinder and a plywood square, inside was a sleeve of black paper hiding the little bunny that had been sitting in the box from before the show started, gently shivering with fright.

My interest in magic tricks gradually developed into a curiosity about psychic phenomena. Like Harry Houdini (!) I turned more to investigation and experiment. I hypnotised my younger brother Jackson when he was still a child, which did not endear me to Isabel, my stepmother or my father.

At the end of our road on the Springwell Estate lived a more serious psychic researcher and one evening, because I was the local conjurer and friendly with his son, I was invited to a séance, not an unusual event in the north of England in the middle 50s, when contact with the other side seemed to be a regular occurrence.

I was introduced to a clairvoyant, a middle aged man, he had travelled from Northumberland to meet us. When put into a trance by the researcher, this psychic, quite a tall man, underwent an amazing physical transformation – he became smaller, stooped and much older and most remarkably, Japanese-like. He spoke to me about my future – instead of looking up to him as I had when we first met I found myself looking down at a much shorter man. I wanted him to tell me that I would be a successful magician. “No,” he said. “But you will be OK and you will be making –” here he gestured with his hands, describing spherical objects. “These things,” he carried on, “but I don’t what they are.”

I was disappointed at not being told what I wanted to hear. So I dismissed his predictions. Shortly after this event, I began Art School and started to make objects that were difficult to describe!