West Yorkshire – Conservatoire of sculpture.

In this chapter I have included texts written by others about my practise as a sculptor. These are Introductions to three exhibitions held in recent years in Leeds, Huddersfield and Wakefield. The metropolitan county of West Yorkshire is the place where I have been informed and encouraged by the many splendid sculpture exhibitions at the YSP and HMI and where I have had some modest successes.

Those who preside over the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, the Landscape for Art (Peter Murray OBE, Executive Director; Clare Lilley, Head of Programme and Head Curator; Angie de Courcy Bower, Curator Archive and Alan Mackenzie Sculpture and Estates Manager) are the welcoming allies of sculptors from all over the world.

Of particular interest to me were the exhibitions of: Kenneth Armitage, Eduardo Chillida, Barbara Hepworth, Jaques Lipchitz, Marino Marini, Juan Miro, Henry Moore, Isamu Noguchi, Auguste Rodin, William Turnbull, Fitz Wotruba, Austin Wright, Ossip Zadkine and Peter Randall-Page (who is alive and working well and, as I write this in July 2013, Randall-Page has become an Honorary Graduate of Bath Spa University)

In his address at the Opening of the exhibition Miro: Sculptor Peter Murray retold how Miro – talking to his friend, Sandy Calder – said: “At 55 I am an established painter but a young sculptor, having started late.”

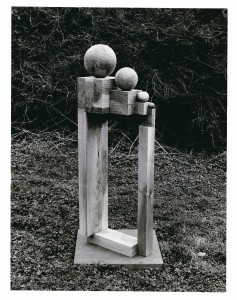

Regarding the Yorkshire Sculpture Park: my carved construction entitled Good Morning World, was a participant in the exhibition Wood at Yorkshire Sculpture Park in 1979, a show that included Peter Startup, David Nash, Glynn Williams, Dave Cobb, Paul Neagu. Some time later Red Head and Spring, were to be seen in the exhibition at YSP Figures In A Garden 1984 selected by Edward Lucie Smith and Glynn Williams, also included were Leonard Baskin, Ralph Brown, Eugene Dodeigne, Lee Grandjean, John Paddison and Gordon Young.

The Hepworth Wakefield is a fine-looking building with beautiful galleries displaying, among other things, the especially splendid collection of Barbara Hepworth plasters. I was on my way to Leeds Art Gallery for the prizegiving at the Northern Art Prize 2011 (in the event my choice for the prize, the short-listed artist Liadin Cooke, did not win).

As an additional incentive to leave the M1 at Junction 39 for The Hepworth, was the exhibition of new paintings by Clare Woods. Both of these experiences afforded me great pleasure and this was crowned with a fortuitous encounter with the artist – Clare Woods that is!

The Arts Council Collection opened a Sculpture Centre at Longside, Yorkshire Sculpture Park in 2003, funded by Arts Council England with the support of the Henry Moore Foundation. The Centre offers storage facilities and provides the resources for conservation and to facilitate loans across the UK and abroad. Next door to the Centre is the Longside Gallery – where Natalie Rudd is the Sculpture Curator – it is a unique space for exhibitions, it is used on an alternating basis by YSP and the Arts Council.

I was at Longside to select work on loan for Corsham Painters and Sculptors – Revisited, in particular a sculpture by Bernard Meadows (a former teacher at BAA), a bronze entitled Armed Bust Version II, 1961. As well as another bronze Orb 1959 by Hubert Dalwood (a former student at BAA).

On my list for the Corsham show I had placed, not as a priority but as a possibility, my own stone carving Two Heads are Better than One. At Longside this mid-seventies sculpture looked better than I had remembered it. Having returned from a spell on loan to a hospital, it had weathered well and had garnered an extra plinth, a stone slab of elegant proportions that enhanced the sculpture. What else was at Longside? Ziggurat, made in 1965, a resin and fibreglass cast with an added wooden frame and 4 Spheres and 4 Cubes, my walnut masterpiece of 2006. Representatives of three decades of work by the same artist. Not that you could tell this by looking at them!

Sculpture in the Age of Aquarius – 1970s Sculpture in the Arts Council Collection. This was a one-day workshop at Longside Gallery in December 2005, curated by Dr Jon Wood, Research Co-ordinator, Henry Moore Institute in Leeds. On show was sculpture by Ivor Abrahams, John Davies, Garth Evans, Katherine Gili, Peter Hide, Michael Lyons, Michael Pennie, Nick Pope and Anthony Smart. Spending the day with this group of sculptors recalled my connections with them over such a long period, I had worked with most of them. As an art school colleague, as a teacher and as an exhibitor. Thirty years after those lively disagreements as to which path was best for sculpture, we met again – our differences not forgotten but moderated by time. It was a pleasure to re-engage with this Fellowship of Sculptors. A generation of sculptors who had worked on with quiet persistence, realising long ago that it was the work that mattered and not its proclamation.

Jon Wood, wrote that: “the 1970s was an intriguing decade for sculpture, witnessing a number of highly influential books (Elsen, Tucker, Krauss), important exhibitions (from Expo’ 70 and British Sculptors ’72 at the RA, to ‘The Condition of Sculpture’), the Alistair McAlpine gift of sculpture to the Tate Gallery in 1971, and the foundation of several outdoor sculpture projects (Peter Stuyvesant Foundation City Sculpture Project, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Grizedale and the Silver Jubilee exhibition at Battersea). It was also the decade in which the Henry Moore Foundation was established.” “Despite this, the work of many sculptors who emerged and were active in this decade in Britain is not very well known today, compared to that of the generations who preceded and followed. This workshop is designed to rectify this and allow the opportunity for students to learn more about the full range of sculpture that was made in the 1970s. We will ask what happened to sculpture in Britain between the ‘New Generation’ work of the 1960s and the ‘New British Sculpture’ of the 1980s? Looking at, but also beyond, the work of well-known artists such Gilbert and George and Barry Flanagan, we will ask if there is what we might tentatively call a ‘lost generation’ of sculptors active in the 1970s? What was being made ‘after Caro and before Cragg’, who was making it, what were its concerns, how was it being written about and where was it being shown? How was sculpture being taught in the art colleges around Britain then and what reputations were being forged and what histories articulated? How were sculpture’s definitions and boundaries being contested, consolidated and further explored in the studios and gallery spaces during that ‘introverted and self-questioning’ decade?

Some four years later Jon Wood wrote of my exhibition in the Henry Moore Institutes’ Library: Made while the glue was drying: New work by Michael Pennie

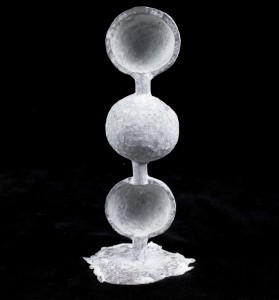

“This display consists of eleven new works on paper made in 2008 and a small group of sculptures. Although they are prints and bronzes, each of these works is unique and not part of an edition. One of the reasons for this is the circumstances of their making. The lino cut prints were made, in short bursts, whilst the sculptor was waiting to finish other larger works. They thus inhabit the spaces between the stages of making sculpture and, as two dimensional works made in the pauses within the production of three-dimensional ones they mark the creative moments that can occur between media and processes. This gives them a liberated and informal quality. Some are intimations of works to be made in the future, whilst others are responses to work in process or reflections, made from memory, on older works. Like his wood carvings they were made by cutting into material and Pennie used a child’s printing set for the purpose, cutting prints for the first time since 1955. The sculptures on display here reveal a similar interest in process, the impromptu and the hand-made. Since 2005 Pennie has been making such small bronzes in his studio, using a small foundry furnace, and taking on all stages of the casting and finishing process. Some are more finished than others and many reveal traces and means of their own production, such as risers and pour tubes. Seen as a group they have interesting blend of planning and experimentation, of passion and modesty: hand-held homages to sculpture and sculptors he has enjoyed over the years, from Cy Twombly and Brancusi, to African sculpture.”

Concurrent with Made while the glue was drying: New work by Michael Pennie atLeeds, was a second exhibition Carving and Casting in Concert – Sculpture by Michael Pennie, to been seen and heard at Huddersfield Art Gallery. In his introduction Robert Hall, (formerly Principal Visual Arts Officer), wrote:

“Following over fifty years of sculpture making the recent changes in Michael Pennie’s practice – from carving wood based more or less on the human figure on a large scale and influenced by West African art – to casting small scale bronze sculptures with echoes of minimalism within a modernist aesthetic – would appear to represent a fundamental shift in his career. However, it is clear that his earlier work always maintained an abstract focus on primary structures and the recent work still relates to the scale and proportions of the figure. One fundamental aspect of Pennie’s work is the way in which it retains the evidence of its making – not just the visual evidence of technique but, as here, also in the sounds of construction in the studio and workshop. Pennie’s beloved Lobi sculpture from West Africa retains an essentially functional aspect and combines craft skills with the physical participation of the ‘user’ in a range of artefacts including musical instruments. He is keen to draw links between the physicality of music making and sculpture making, and this is indicative of his sympathy with the traditions of African sculpture rather than the European classical tradition and its Renaissance definition he was encouraged to embrace as a student in the 1950s and early 60s.”

“In a long career of making and teaching Pennie has always been a reflective practitioner – one of the demands of teaching from which he retired in 2001– keen to address the specific issues and concerns of his activity, and of his growth as an artist. Key issues have been the balance of abstraction and figuration and their formal equivalents, scale and the processes of making. Increasingly he has become interested in how the works are displayed singly and in groups, and how this impacts on meaning and reception, developing the notion of conglomeration from his exposure to the visual power of works grouped together in shrines in Ghana and Burkina Faso. Recent collaborations with musicians and composers Cameron Jenkins and Nick Franglen have explored the relationship of image and sound resulting in three ‘sound parts’ to accompany Pennie’s wood and bronze sculpture, displayed here. One important aspect of Pennie’s work has been the concept of distillation, the reducing of the raw material to reveal the essence of the work, and its association with alchemy and the transmutation of materials.”

“My sculptures are distillations…”

Robert Hall continues. “This process involves an initial mental image at the beginning of a multitude of visual decisions, including aspects of surface and colour, often obliterating the given surface by painting and staining it to regain a sense of the whole. The process involves a continuing dialogue between the carver and the material. This way of working is also reflected in his cast bronze pieces and the speed of their conception, initially modelled in wax as three dimensional notes or sketches, and in some cases coloured with oil paint.”

The one hundred bronzes were made almost without hesitation, concerned less with the individual and more with the populace.