Most likely it was Marlene who spotted the Flat to Let notice in The Chippenham News. I went to Marshfield to look it over. The Malting House, 78 High Street, stood in the middle of a long terrace of once grand houses, a couple of shops and three pubs. One hundred and three miles from Hyde Park (according to the milepost at the beginning of the street). Number 78 is a three-storey house, if you count the attic space. In 1977 the tenants from the ground floor had moved upstairs, leaving a living room and bedroom at the front, two more bedrooms at the back and a kitchen and bathroom as well as a garden with shed: all empty – except for the shed – but in a mess. I spent Easter cleaning and re-decorating all of it.

For some weeks I was alone, banned from seeing my children and shy of friends; I was isolated after my flight from Corsham.

We paid a deposit and rent in advance and I was beginning to believe that this was truly a joint venture, but I was still apprehensive and always aware that our plan to ‘be together’ might be blocked midstream. Back then I was not so used to Marlene’s determination!

During that Easter break from college I painted high and low all day – early morning until late at night – becoming too tired and too anxious to sleep. The stress of my marriage breakup and not being able to see my children was beginning to catch up with me and my nights became shorter and shorter until, in desperation, I asked the local doctor for a sleeping tablet: one single pill so that I could rest and relax and take a respite from anxiety. This Marshfield doctor was both bad doc and good doc. He berated me, in no uncertain terms, for poisoning myself with pipe tobacco, abusing my body with filthy nicotine! Only after I promised to take note of his harangue did he agree to prescribe medication that would settle my nerves and help me to sleep during the difficult waiting time until we were together.

My impression of Marshfield was that it was a transit village; a refuge for ex-husbands or wives. A place to try out new partnerships before moving on to a more settled relationship. The sculptor John Huggins and Nicki were good examples – coincidentally, they lived next door for a while.One day I met John in the street, in light rain. John was exploiting the wet weather to wash his vintage silver Porsche.

It was a sculptors’ place then. At one end of the village is Ken Cook’s foundry and Anne Christopher’s studio, both close friends of John Hoskin. From time to time we saw Ralph Brown and Carrie, clients of Ken, looking in the window of the second hand shop across the road from us. Sarah Paget (a former BAA sculpture student) and family lived across the street from No. 78 (and they still do).

In theory, I was to use the shed in the garden for making sculpture, but it was entirely full of beer bottles and wine bottles. The most well known tenant of The Malting House was Dylan Thomas, he lived there for about three months in 1940. The musician William Glock was another resident around that time. The bottles may well have belonged to them. The third bedroom became a workshop while the second became the children’s room for Helen, Rachel, Daniel or Christopher, when they wished to stay with us.

For Marlene the transition from Corsham to Marshfield was via Cheltenham where she spent a short while with her Aunt Lor. I spent a weekend there and returned to Marshfield more alone for having been very much together: alone was painful.

(Dear person who is reading this text, at this juncture you may enjoy listening to Max Bruch’s Violin Concerto No. 1 Opus 26 in C major 11 Adagio played by Jasia Heifetz and conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent. This was my music for those awaiting days, played morning, noon and night, an apt concerto for the lovelorn.

We were happy living at Marshfield. Marlene had arrived (conveyed to number 78 by her son Phil) the day after her fortieth birthday with all her possessions: two carrier bags (full but not overflowing). It was not much of a bottom drawer to start her new life with her sculptor, part-time lecturer, forty year old lover!

The couple that had moved upstairs at The Malting House fared less well. Their relationship did not prosper, and in a very short time the sounds from upstairs had changed. The rhythms of their connubial bliss – that had an inhibiting effect on our own connubial bliss – gave way to late night arguments, shouting and screaming. It was a state of affairs that escalated and eventually ended with the young man’s suicide. There were police at the house for a while. The body was stretchered out of the front door. Another small scandal that added to The Malting House’s doubtful reputation.

Recently, that is in 2010, I revisited my sculpture Bootmark, a work that I had started in the flat at Monks Park and completed at Marshfield. The newest version updated after more than thirty years, sits behind me now as I write this.

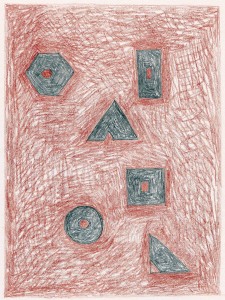

I made Arbor at Marshfield, a construction from very dry and pale walnut, with partly carved pieces. It has a rectilinear frame, enclosing a small cube, surmounted by a sphere, both forms resting on a circular base. A sculpture ‘assembled’, carved, dowelled and glued at Marshfield from parts cut out in the Academy workshops at Beechfield. I entered Arbor, a ‘togetherness’ work, for a South West Arts Award. My sculpture won the First Prize of £500. Patrick Hughes, a fan and Panel member, might well have had something to do with this success. Thereafter I was asked to join the South West Arts Panel, travelling by train to Exeter with Jos Tilson. On the agenda of my first meeting was an item that would determine how these annual awards should be spent – for materials or studio rent, but not as a deposit for a second-hand car. As the owner of a recently purchased second-hand Pallas Blue Citroen DS, my blushes were spared when the Panel voted not to interfere with how successful artists should use their prize money.

One Saturday morning while Marlene and I were living at Marshfield the postman delivered, with some difficulty, a brown paper envelope. It landed on the hall mat, somewhat dishevelled and badly torn; it had been squeezed through the letterbox. The envelope was bulging with £5 notes – eighty in all! This surprise bundle of cash came from Virginia Johnson, almost four years after Brian’s death. A brief note referred to some unexpected royalties from Brian’s books that she had passed on to me in Marshfield and my family in Corsham. Clearly Virginia knew of my marriage break up.

This astonishing donation was most certainly needed; it was an act of generosity offered with an appreciation of the difficulties facing us all. I have always credited Virginia with the perception that during the short time she was with us at Pound Pill she intuited that ‘something was going on’ and that a change in my marital status was imminent, but not as traumatic as the change in her life, of course.

Anyway, at the time we owed money on the car, on our not so new Citroen (coincidentally the same model as Virginia’s). I had become the victim of ‘modern banking’. Mr Bailey my ‘good money’ fairy retired from Lloyds Bank. Mr and Mrs Bailey had lived upstairs ‘over the shop’ in the High Street for as long as I could remember. They were almost the part of the family, (not that there were many parts to my family), who would not see us go without. The new manager, both faceless and nameless to me, altered my overdraft facility from a low to a higher interest rate. I confronted him, threatening that I would take my overdraft to another bank! He was unmoved.

Virginia’s gift might have made us friends forever and I regret that it did not. She had her new life with Gordon, I had my new life with Marlene; Brian’s death was the end of that chapter. I was distressed at losing a friend – a man that I cared for and an artist I esteemed – but I was also angry that my recently discovered mentor had abandoned me so soon.

Marlene and I were together in the Malting House from the end of May in 1977 until February 1978, when we moved to Atworth.