At Bede Grammar School, as well as making drawings, I began to paint with gouache: I did this at home too. The recent death of Elizabeth Taylor has reminded me that she was the subject of my major opus, a painting that I took to Sunderland College of Art for my entrance interview. A portrait of my favourite star, costumed as Rebecca for the film Ivanhoe. I had copied it from the front of the magazine, Picturegoer.

After O’ levels, (given my basic GCE results and the fact that I thought I was good at Art), I decided to go to Art School. My father now married (to another Isabel, spelt with an ‘a’ instead of ‘o’), approved of his son going to College, although I believe any other college and any other subject would have been preferred. For a short while brother George, who did not go to Grammar school, went to college too, to study architecture.

Arriving at the Art School I came upon a tallish man – somewhat unkempt – wearing a long-sleeved undergarment, navy blue Melton trousers, unlaced hob-nob boots and peering over rimless glasses. He was issuing instructions quite forcefully to a group of students who were busy hanging their work in the reception area of the college. This was Harry Thubron, in charge of the Fine Art Course and the absolute personification of my imagined ‘artist’.

During my interview with Principal Norman, who was very properly dressed, (we had another encounter several years later in Liverpool), he unrolled my drawings of boxes and paintings from photographs, onto his desktop. Having a will of their own and preferring to remain hidden (out of modesty), they rolled themseves up again when the Principal let them go!

Clearly not impressed with my submission, he suggested I enrol on the General Course, a preliminary year which served as groundwork for the two-year Intermediate Course. This in turn was preparation for a more specialised two-year Diploma, the NDD.

On the morning of Enrolment Day, (an autumnal Saturday), I was walking from the town centre to Backhouse Park when I met Stan Mitchell walking the other way. He was senior to me when we were at the Grammar School and he had just enrolled for the Ceramics course. His advice to me was, “Put down the Intermediate not the General.” This I did. Thus the pattern of my career as an artist was established; crucial decisions were made by happenchance, accident or fluke!

My father was pleased and surprised at my acceptance. The only painting he had seen me accomplish was decorating the prefab that we had recently moved into. Wall after wall of cream paint, coat after coat onto thirsty absorbent boards.

The Fine Art Course was held at a house called The Cedars, across the park from the main college building. There were three carvers – Fenwick Lawson, Hughie Clarke and me. For the Intermediate examination, taken two years into the NDD course, I chose wood and Hughie elected for stone. With Herbie Simpson’s help I carved a stretching cat in beech wood. I made it well enough to pass the exam. My first finished sculpture.

Encouraged by my success as a woodcarver, I became more ambitious. In fact, too ambitious. I began work on a life-size torso, following Fenwick. I think this carving was an excuse to use my adze, it had a sharpened blade set at right angles to a very long shaft – but where did I get it from?

One leg or thigh forward and one back. I chopped furiously, then rolled the big log over and attacked it again, more ferocious carving – only to find that I had been hacking at the same leg, now sharpened to a point. In my zeal, I had virtually amputated one leg from the carving and very nearly one of my own – slicing through my trousers as I swung the adze!

After this disaster I abandoned the carving, having been ‘advised’ by Thubron at the top of his voice, “To work in clay first.” (as preparation).

In the spring Harry Thubron, Bill Archer and Bob Jewell would set up large canvases on easels in the glass-covered stable yard. They would begin to paint, working on their submissions to the Royal Academy Summer Show. I remember one time that Thubron’s painting was a post-impressionist portrait of a dark-haired student; Bob painted landscapes with pit heaps and pigeon ‘crees’ and Bill Archer did his usual seascapes from postcards.

In Year Three everything changed, figurative work gave way to abstraction. Basic Design took over when the Pasmores came to the Northeast and settled at the University in Newcastle. Suddenly the pink blossom on the trees in he Cedar’s garden brought early Mondrian to our attention.

Thubron sent me to Newcastle, to the Hatton Gallery, to study the student work that heralded this new formalism. When I reported back to Sunderland I was chastised by Thubron. Apparently, I’d missed the point. I was unimpressed with the cubes and spheres and drawings of ruled lines in black ink. I was indifferent to Pasmore’s ‘modernism’ but Thubron saw this new doctrine as full of opportunities and possibilities.

Soon afterwards Wendy Pasmore joined the Sunderland teaching staff and became my tutor. I was quickly charmed into changing my mind completely and I began to make constructions. Working with dowel rods, painted white, with some coloured intervals of red, blue and yellow plywood, my construction was given pride of place in the Art School exhibition at Sunderland Art Gallery, Sunderland’s response to Newcastle. A photograph of my three-dimensional Mondrian was featured in the Sunderland Echo and brought me a whiff of celebrity. There was no subject or content to this sculpture although it looked as if some intelligence had been at work – I had enjoyed making it.

Through Wendy, Hughie and I had a trip to the New Town of Peterlee. Victor Pasmore had a hand in the design of the landscape and responsibility for the recently restored Apollo Pavilion. To add some spice to Peterlee, several artists teaching at Sunderland Art College were encouraged to live there, including Harry Thubron and Bob Jewell.

With Wendy Pasmore’s guidance, we began to work on architecture and sculpture together. My main opus was a large plaster façade, pierced with openings as doors and windows, with a small sculpture – made as an integral part of the whole – sitting in front of it. Corb for Corbusier and Mies for Mies van der Rohe were the buzz names, for me especially, because my brother was studying architecture at the time, (by now doing a Correspondence Course). We were encouraged in this New Art by the currents from the Festival of Britain that were at last reaching Sunderland, only four years later. More than 50 years on, in recent work, I am again piercing walls with windows and doors, albeit with a less optimistic view of the world.

After Thubron left Sunderland to carry the torch of Basic Design to Leicester, he returned to the Cedars briefly to fulfil his commitment to three weekend courses. I acted as his technical assistant – brazing, casting, mixing plaster and sawing wood. I was probably helpful but not that competent, I was certainly enthusiastic, as I was being paid.

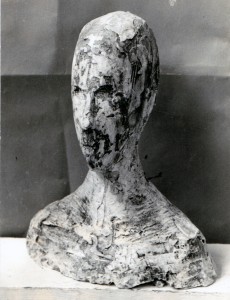

Working with Thubron and Wendy Pasmore loosened my allegiance to the notion of depiction. I began to realise that form, proportion and the relationship between the parts of a sculpture were paramount; sculpture was a visual not a literal language. Nevertheless, for my final year, after Thubron went south, I reverted to looking again at Marino Marini; I made ‘girls’ in direct plaster, mostly based on drawings of Marion, our young life model. She was a dancer, and not someone who should have had to earn her living standing still. My sculptures were more Degas than Marini. Marion was the opposite to Wilkie, who was our other model. Wilkie was at least a pensioner and claimed that she had worked with Rodin.

Some years later Thubron was a Selector at the Young Contemporaries Exhibition. I met him when I was submitting my sculpture. At that time he was impatient with the work produced by the London schools, but stressed the importance of getting my degree. “What you want is the piece of paper,” he said. Disdainful of the post Anxiety of Fear figurative work from the RCA, he pointed to a ‘walking man’ sculpture to emphasise what was wrong and out of date with it. I did not admit to him that the work in question was mine!

I was to see Thubron one last time, at Corsham. He was there to talk to Bath Academy students, during the restless summer term of 1968. In our conversation afterwards I learned of his respect for Clifford Ellis.